As part of the recent RBSCG conference, we were treated to a reception at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, and this is me looking at the opulent surroundings of George IV’s music saloon. One of the striking things I learnt from this visit was that the luxurious collection of bespoke designed furnishings and objects that George IV proudly amassed at the Royal Pavilion was completely stripped out and dispersed after his death by his successor, Queen Victoria. The collection that we saw was made of some original objects which had been begged, borrowed and purchased back from their new owners. There were also objects that had no Royal Pavilion provenance but were right for the period, which were on long term loan from other collections such as Apsley House.

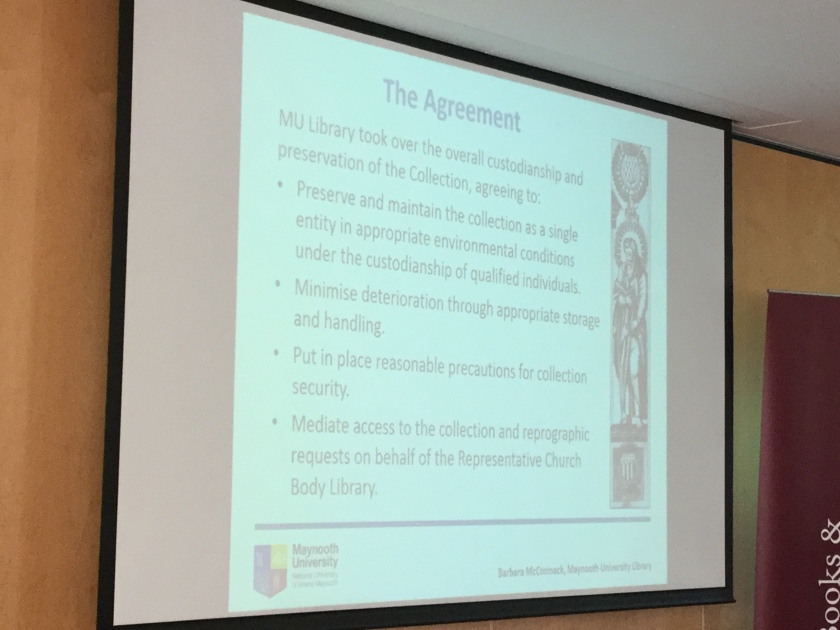

This theme of collection ownership and collection movement was also picked up by a paper on the St Canice’s Cathedral Library Collection by Barbara McCormack. The St Canice’s Cathedral Collection of 3,000 early books, one of the oldest diocesan libraries in the Church of Ireland, was recently moved to Maynooth University . A long term loan agreement was put in place between Maynooth University and the Church of Ireland, where the University paid the costs of moving the collection and conserving it, but now houses the collection at Maynooth for use in research, teaching and exhibitions. The arrangement has borne fruit in new collaborative work going on between the Church of Ireland and Maynooth University, arising from the St Canice’s Library.

Anastasia Tennant from the Arts Council spoke on export controls and tax incentives for the acquisition of mss and books by public institutions. Then Alixe Bovey from the Courtauld Institute spoke about the dissolution of the Mendham Collection – “Reflections on a historic library we couldn’t save”.

Joseph Mendham ( 1769–1856) was fervently devoted to evangelical Protestantism and opposed to Catholicism, and he collected books that had been prohibited by the Catholic Church. Ironically he built up a library incredible rich in early Catholic as well as Protestant sources. After his death his 5000 books were offered to the library of the Incorporated Law Society, which in 1984 decided to offer the collection on loan to Canterbury Cathedral. During this period, the British Library awarded it a cataloguing grant of +30K subject to the condition that the collection should not be sold in future. On 5 April 2012 the Chief Executive of the Law Society wrote to Canterbury Cathedral Library to inform them that the Law Society intended to sell the collection. From this point, the Law Society moved very fast to force the sale and dispersal, which a vocal public media campaign was unable to halt.

Learning points that Alice identified from the story are that the ‘Peoples of the book’ (scholars, students, librarians) are an amazingly networked, powerful community.

All over the world they will offer money and support to save rare books. However if you have a campaign with a single charismatic item, like a Shakespeare first folio, it’s much easier to gather support. Collections are more difficult to ‘sell’, particularly theological collections amassed for reasons that don’t appeal to modern times. Time matters – a campaign should stall for much time as possible. Ironically, a lasting monument to the collection is the Sotheby’s catalogue for the sale, which shows how much cataloguing matters!

Finally Margaret Lane Ford from Christies spoke on practical advice on dispersal from the book trade. She pointed out several existing guidelines for good practice

CILIP Disposals Policy for Rare Books and Manuscripts

MLA (now Arts Council) Guidance on Disposals

Bibliographical Society Libraries at Risk Policy

It’s important to remember that dispersal of libraries has always taken place, and that weeding and management are necessary.

Factors to be considered include :

- Collection integrity

- Relevance of material

- Legal right to deaccession

- Use of the proceeds

- Public access

- Reputational risk

- Duplication

- Copy specific features

The process should be transparent, with clearly stated goals. Bookdealers and auction houses are not the enemy. They are brought in after the decision for sale has been made. Decisions are almost always financial and may be notified to librarians at a very late stage.